Contemporary Commodity Fetishism: First Repression, then Capitalist Realism

For Marx and Engles, commodity fetishism was crucial for a theory of ideology in a capitalist society. For them, ideology was based upon a distinction between the nature of social reality and the widely experienced distortion of said reality by subjects. Their concern was with the social origins of untruths rather than of truths, the origins of the structures which hide the insights of material reality and the inherently social characteristic of said reality. Commodity fetishism for Marx was the commodity form’s ability to distract the social relations and material labor that went into the commodity, from the minds of the consumers. When subjects consumed commodities, there was a social phenomena he saw occurring where there was a collective forgetting, a collective amnesia you could say, of the labor that went into the commodity, and the social relations that allowed the commodity to get to them.

With this, we can see that Marx’s theory of ideological distortion through commodity fetishism can be linked to the Freudian notion of repression. Marx’s term “fetishism” through its advocacy for the existence of the irrational, anticipates Freud’s analysis on a striking level.

Marx’s analysis of the cultural phenomena he labeled commodity fetishism implies a psychology here: custom set routines in a given society drive from the unawareness of the full nature of these routines. For something to be an unconscious habit, one inherently cannot know the nature of this habit and what it exists to do. In this way, there is a link between custom and lack of awareness, so that an unconsciousness is built into the accomplishment of social customs that reproduce ideology.

In contemporary capitalism, the economic system and its relations that it creates base themselves off of the absolute fulfillment of pleasure in the form of consumption. More so, consumption patterns and what subjects consume becomes an identity creation action. Objects reflect identity, and in turn, now impacts social relations. If the commodities are to be consumed as items of pleasure and as confirmations of the identity of the consumer, then the consumers must routinely not think about the labor relations involved in the production of what they are consuming. Inherently, if the relationship between the label and the retailing outlet in which the object is purchased can also be imagined in relation to my sense of self, then the social relations beyond that label are forbidden territory. My goods, in order to be mine, must be separated from the bodies, and thus the relations, which have created them. Clearly, Marx’s commodity fetishist theory remains relevant, and in my opinion, on an even greater level.

Now, the question becomes, how to conceive of this routine of collective forgetting of the relations and labor that go into the commodity from a psychological perspective. A link can be made with Freud’s concept of repression. Freud’s concept of repression literally indicates the driving away of a disturbing thought, especially a desire, from conscious awareness into the possession of the unconscious, motivated by the impulse not to experience unpleasure. However, Freudian theory cannot be applied in an orthodox and straight-forward way when dealing with the altered conditions of contemporary capitalism. It must be reinterpreted and use a discursive psychology and conversation analysis, which would allow us to analyze the sorts of social habits and rituals that lead to this collective amnesia and forgetting, or, commodity fetishism

For Freud, the history of society evolves, transforms, and progresses, in terms of the increasing repression of pleasure. Yet, in late capitalism, there is a different psychological dynamic where the modern market necessitates a deployment of the pleasure principle for its own perpetuation. Seduction rather than repression is demanded for late capitalism, in such that the consumer must be constantly seduced in the insatiable pursuit of pleasure. However, if this forgetfulness of the labor relations behind the commodity, or at least a distraction from them at the point of consumption, is a component of this constantly lived seduction through consumption, then repression may return in a changed form. The economically determined pursuit of pleasure may demand a repression of the ego in order to push out of consciousness those labor relations and structural realities that if entered into conscious thought, would spoil the pleasure gained by consuming.

When Freud analyzed the causes and effects of repression, he didn’t say much about the actual processes of repression themselves. He wasn’t interested in examining the possible skills which need to be accomplished for people to be able to repress disturbing thoughts, rather just the situation(s) that give rise to repression, and the effect on the psyche of this repression. Moreso, Freud in his metapsychological analysis, made a rigid distinction between the conscious and the unconscious. However, routines and habits suggest states of mind which transcend that barrier between consciousness and unconsciousness that Freud supposed. The routine forgetfulness that is commodity fetishism that Marx wrote about alludes to a collective ideological practice of repression rather than an individual phenomenon. A good example of this collective ideological practice constituting habits and rituals can be seen in the material ways ideology presents itself in society, ie: nationalism presents itself in society: nation’s flag hanging outside public building x, a material object representing an ideology that is always present in the lives of the contemporary citizen

The collective forgetting that Marx talked about is not just routine but also appears to be “willed” and socially motivated, in a way which links it with the Freudian analysis of why repression occurs. This linkage between Marx’s theory of collective forgetting and Freud’s concept of repression depends upon seeing the skills of repression themselves as being socially acquired, making it so our notion of repression here must be reinterpreted as a social concept.

Sets of routines, because of their habitual nature, necessitate a drawing away of attention from other possible thoughts, and can maintain the sort of social amnesia put forth by Marx. This pattern is found in the routines of language. The acquisition of language depends upon acquiring habits of conversation, and this involves the construction and negation of desires. In consequence, repression, or this form of social forgetting we are putting forward, is built into this fundamental shared human routine, the routine of talk. This approach derives from discursive psychology’s goal to understand how the explicit social use of language constitutes internal conscious states of mind. The process of repression may be constituted within discursive activity and ritual, so much so that we can talk of a “dialogic unconscious” in the way Billig uses it in 1997. This approach emphasizes the practical activity of conversation, and to use the Saussurian distinction, is very different from the Lacnian project emphasizing the structure of language in and of itself.

Language, in its use, is repressive in the Freudian sense as well as expressive in the conventional sense. While learning a language, subjects do not merely learn a system of signs, or acquire particular sets of discourse. Subjects also learn something more fundamental, the skills to speak in dialogue, which is the means by which any “discourses” and their rituals are acquired and practiced. These dialogic structures and the learning of the skills to be under said structure require learning the complex mechanisms of interpersonal speech, which are reproduced in expressive conversation. Dialogue in the end is based on subjects taking turns and the sequenced structuring of discourse beyond that as well lies at the center of conversational interaction. More importantly though, the codes that dictate this turn-taking structure and all that lies beyond it must be acquired by the subject, otherwise the ability to hold social conversation, and thereby action, is impossible. If these discursive codes are broken, like if speech is delivered with inappropriate info, pitch, or speed, the goal of discourse and what it accomplishes can be threatened. To protect from this, there are global cultural phenomena in which each set culture has their own codes of politeness, rudeness, speed, pitch, etc, so that speakers will end up regularly policing their own usage of dialogue in conversation. These structural codes and cultural rules create a paradox in which these codes of politeness themselves create the possibility of rudeness. Dunn 1988, and Billig 1998 show studies of children acquiring language while demonstrating that for these children, after they are taught these discursive codes, rudeness and disobedience from these codes becomes a temptation. This temptation is initially punished, and then later, the codes are internalized and then resisted routinely by the subject’s own self-policing. Later on and naturally after this, the codes become learned habits, performed non-consciously during conversation.

Marx realized that the habits of ideology can accomplish a social forgetting, and the aspects of language are crucial in this respect. Discourse and linguistic codes that arise within society constitute the desire to disobey said codes which must be routinely repressed. This also provides rhetorical devices which enable reproduction in a more elaborate and complex form. For example, parents are constantly using these techniques of rhetorical policing and reinforcement of codes to direct conversations away from socially undesirable themes when holding discourse with kids. This outward discursive control of parent to kid was ignored by Freud in his account of oedipal development, yet can be seen in his case with Little Hans. With this understanding, we can see that the child is provided with rhetorical models for changing the topics of conversation from a very young age. This is important if we understand that outward dialogue, and especially the rhetorical models of argumentation, provide the very discursive models for our internal conscious thinking, or even the internal debates we hold with ourselves The rhetorical devices for when to change topics, and how to do so, that we are given from a young age, are internalized and reproduced in our own inner mental life, which shows how we may attempt to change the subject of our own thoughts Here, we may be able to provide an answer to the question Freud was unable, “how does the young child in the Oedipal stage learn to repress the unwelcome thought” The answer we have reached to is: by listening, coping, and internalizing the talk of adults.

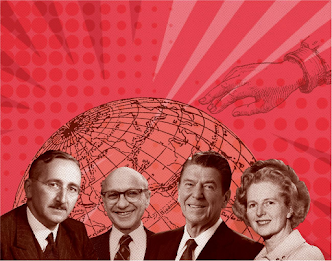

In contemporary capitalism, Mark Fisher speaks of a cultural phenomena of capitalist realism. For Fisher, “Capitalist realism refers to the widespread belief that there is no alternative to capitalism — though “belief” is perhaps a misleading term, given that its logic is externalized in the institutional practices of workplaces and the media, as well as residing in the heads of individuals.” (Fisher 2012) Fisher then gives an example of how this phenomena reproduces itself in discourse, writing, “This means that, however much individuals or groups may have disdained or ironised the language of competition, entrepreneurialism and consumerism that has been installed in UK institutions since the 1980s, our widespread ritualistic compliance with this terminology has served to naturalise the dominance of capital and help to neutralise any opposition to it.” (Fisher 2012) Capitalist realism and capital’s ability to control discourse patterns, can be utilized in our analysis of commodity fetishism and how it reproduces itself in discourse. In our modern society, the relations behind the commodity aren’t even close to hidden from us. The productive origins of commodities basing themselves in poverty, the brutal working conditions and exploitation that goes into it, aren’t hidden from us at all. We hear about the child labor, see the disturbing pictures of the Third World, and the disgusting sweatshops that produce our oh so desired clothes. Yet, when buying a commodity, most still do not imagine the commodity relations behind them. We seem to distance ourselves from this information, never connecting it with our own commodities that we see as ours.

This is because of three things. One, the subject sustaining commodity fetishism completely destroys the Freudian dialectic between pleasure and social duty. In the societies Freud analyzed, the pleasure principle had to be repressed to fulfil your social duty in the reproduction of society and the relations that hold it up. Yet, as Billig points out, consumer capitalism structures itself around the absolute seeking and fulfilling of the pleasure principle. This contemporary society then is a completely different structure of society to those that Freud analyzed. Now, social duty, or your certain way of reproducing the structures society builds itself on, does not run in opposition to the pleasure principle, but the fulfilling of the pleasure principle necessarily is your social duty now. This dichotomy, and thus the dialectic Freud showed in his theory of society’s progression, is now destroyed here.

Secondly, when we internalize discourse codes as kids growing up in contemporary capitalism, we are internalizing the speech that capital censors. Kids internalize the notion to never ask about pay, or ask about working conditions, as that is seen as “rude” and “disrespectful.” Since capital has invaded the psyche and its desires, capitalist realism invades the minds of all adults, and in turn reproduces itself when these adults reproduce the discourse codes of the capitalist society onto the child class.

Lastly, even if one breaks this ideology of commodity fetishism, Zizek shows how in contemporary capitalism, it still doesn’t even matter, “...today's society must appear post-ideological: the prevailing ideology is that of cynicism; people no longer believe in ideological truth; they do not take ideological propositions seriously. The fundamental level of ideology, however, is not of an illusion masking the real state of things but that of an (unconscious) fantasy structuring our social reality itself. And at this level, we are of course far from being a post-ideological society. Cynical distance is just one way ... to blind ourselves to the structural power of ideological fantasy: even if we do not take things seriously, even if we keep an ironical distance, we are still doing them.” Fisher says about Zizek, “Capitalist ideology in general, Žižek maintains, consists precisely in the overvaluing of belief - in the sense of inner subjective attitude - at the expense of the beliefs we exhibit and externalize in our behavior. So long as we believe (in our hearts) that capitalism is bad, we are free to continue to participate in capitalist exchange. According to Žižek, capitalism in general relies on this structure of disavowal. We believe that money is only a meaningless token of no intrinsic worth, yet we act as if it has a holy value.” We can see that one can internalize anti-capitalism after breaking from commodity fetishism, yet through action and our reproduction of capital’s social structures, this mental anti-capitalism doesn’t actualize itself. Anti-capitalism has been incorporated into commodity production itself, so breaking away from ideological capitalism and its fetishism of commodities doesn’t destabilize capital at all.

In the end, I ask is that we consciously make the decision to remember the conditions of daily exploitation that create the commodities we hold so dear. We should remember, not abide by this collective amnesia, that our fetishized commodities are produced by unnamed “others”. Our routines of daily life in late capitalism distract us from this remembering, and allow us to habitually forget that our possessions have been produced by the labor of repressed Others. Let’s remember them. And if you do remember them, let’s also remember Zizek, who shows us that if we do begin to remember these exploitative labor relations, let’s begin to not hold these objects so dear and reproduce capital’s consumerist cultural structure. And finally, let’s maybe actualize this mentality, instead of doing capital’s work ourselves and reproducing it.

Comments

Post a Comment